Facing the Shadow

A Self(ish) Spirituality Reflection for Lent on Luke 15:1-3, 11b-32

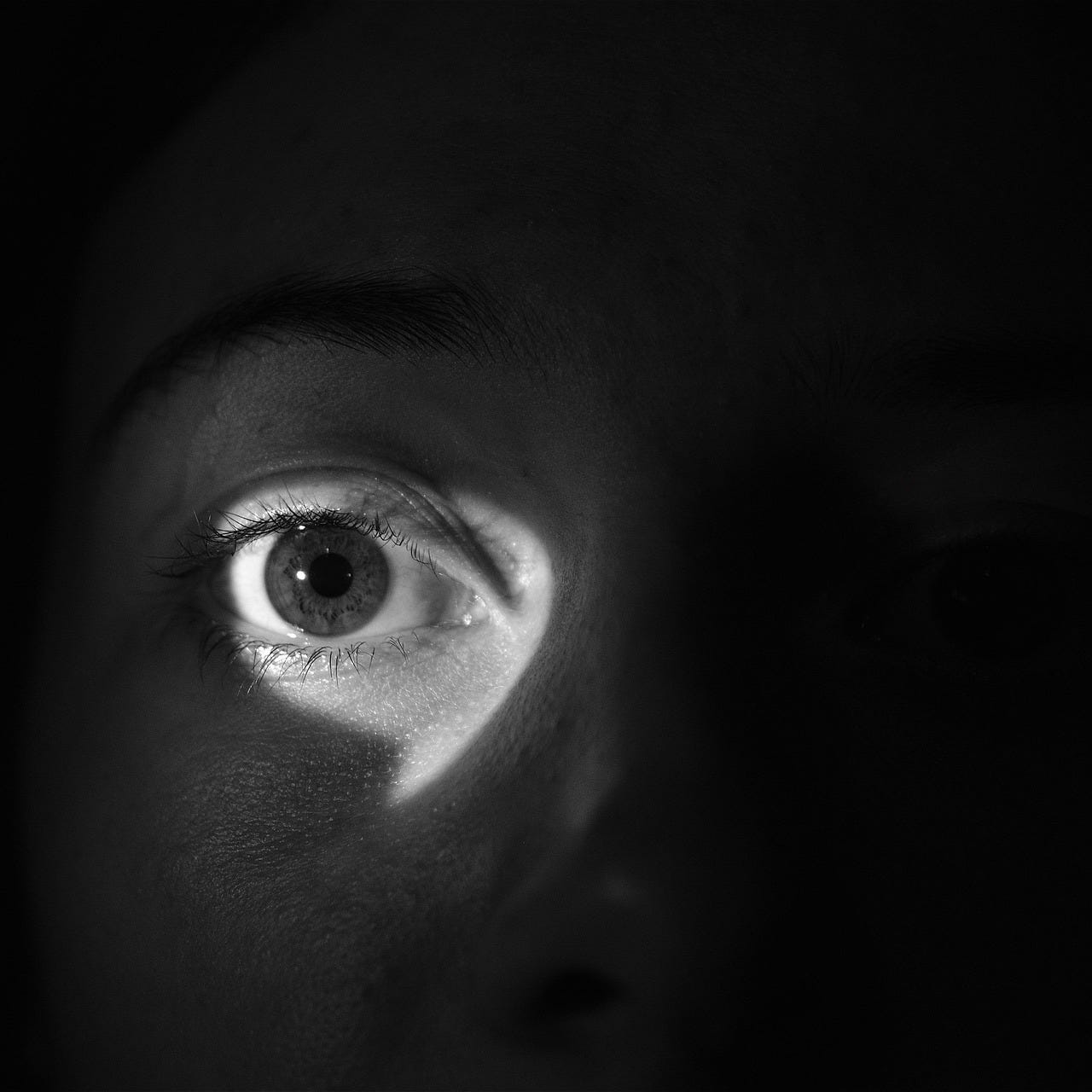

THE SELVES IN THE SHADOW

Her path to healing could only be found when she acknowledged, faced, and listened to the voices in her head.

Eleanor Longden’s childhood trauma did not immediately reveal its impact on her life. It was only when she started studying at university that the voices began to speak. But when they did, their presence led to her being institutionalised, disbelieved, and dismissed as insane. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia and at one point was left in a padded room in a psychiatric facility with no hope for any kind of sane and meaningful life. Eventually, she was discovered by a psychiatrist who listened to her, worked patiently with her, and taught her to listen to and manage the voices as a way to address their anger, threats, and debilitating impact. She still hears the voices, but she now recognises them as aspects of herself that she has learned to recognise, accept, and integrate; and her recovery has been such that she was able to return to university and graduate with a doctorate in psychiatry.1

While Longden doesn’t ever refer to her voices as her shadow, she does explain that “each voice was closely related to aspects of myself and that each of them carried overwhelming emotions that I’d never had an opportunity to process and resolve—of shame, anger, loss, and low self-worth.”2 Her story is a dramatic and moving insight into the shadow that exists within all of us.

The concept of the shadow was one of Carl Gustav Jung’s greatest contributions to the field of psychology.3 As Roger Wolsey describes it:

According to Jungian psychology, we all have metaphorical masks that we wear and images—our personas—that we seek to put forth in the world for how we’d like to be seen and known for. Yet, the more that we focus on those idealized images, the more we repress the opposites of whatever our preferred images may pop up into our lives. If I want to be known as a “nice, sensitive person,” I stuff and hide away the “mean, insensitive, jerk” parts of me. Those portions of myself that are repressed and denied are my shadow (one of the Jungian archetypes). But the thing is, when we try to minimize those shadows, we actually increase and magnify their power.4

While we may be tempted to think of our Shadow as consisting only of negative or bad parts of ourselves that we deny, it also includes any positive or good aspects of ourselves that we may feel unable to accept or acknowledge.5 The problem with the shadow is that it takes work—which is often painful—to recognise it, work with it, and integrate the repressed parts back into our psyche. Many of us resist doing this work, and the result is that we often project our disowned selves out into the world. As Ken Wilber notes, “in 9 out of 10 cases, those things in the world that most disturb and upset me about others are actually my own shadow qualities, which are now perceived as ‘out there.’”6 (Emphasis in original). This means that one of the most important pieces of spiritual and psychological work we can do—for ourselves and for those around us—is to become conscious of, face, and transform our shadow.7

A PARABLE OF SHADOWS

The Gospel reading in the Revised Common Lectionary for the Fourth Sunday in Lent is what we now know as the Parable of the Prodigal Son. Traditionally, this story is often interpreted as the perfect illustration of how Fall/Redemption Theology8 works. A young man, because of his inherent fallenness (original sin) chooses to trade his comfortable and beloved life for a world of selfishness, debauchery, and excess. When he ends up destitute and alone, he faces his sinfulness and returns home to ask his father for forgiveness. But the father has been waiting and runs to meet his son and welcome him back into the family. In my opinion, this is a rather one-dimensional treatment of this text that misses most of Jesus’ message. While Jesus would not have had this language, it can be helpful to interpret his story through the lens of the shadow—and when we do this, our focus cannot only be on the lost son but must also turn to his older brother.

The younger son has grown up in a home with enough wealth and privilege to have servants, but not enough that the family is relieved of the duty to share in the work of the estate.9 But this young man is dissatisfied, and so he disrupts his family by prematurely taking his share of his father’s inheritance and heading off in search of a different life—and a different self. Jesus doesn’t embellish the story enough to reveal what might have motivated the boy to leave, but most of us have enough experience to be able to relate. Perhaps he wanted more freedom, adventure, experience, pleasure, independence, or autonomy. Perhaps he had never been able to get over the grief at losing his mother (she is never mentioned in the story, so perhaps we can be permitted to speculate and elaborate?). Perhaps he was tired of living in his older brother’s shadow. There are as many versions of this story as there are young adults in the world—and most of those who follow the same path as this fictional young man have not done the work to understand the inner shadow that drives them.

But the adventure does not end well. The mindless escapism leads the young man to ruin and he ends up working for meagre wages and terrible food on someone else’s farm. The pain, humiliation, and regret leave him no option but to “come to his senses” (or back to himself) (v.17) and so he finally faces his shadow and does the work of healing that he has been avoiding.10 He gets honest with himself, takes stock of his situation, and—free of his shadow’s hidden influence—remembers his father’s kindness. He is now able to return home, receive the unexpected, gracious welcome, and settle into a more stable and connected life. This is a parable of grace, yes, but it is also a beautiful parable of the healing power of shadow work.

THE DISOWNED SHADOW

Jesus could have ended his story at this point, but he didn’t. This is the first clue that the parable is about more than a fall from grace and an experience of redemption.

The older brother does not share his father’s joy at the prodigal’s return. He has been good. He is the faithful, reliable, stable, obedient one. But he is also a martyr. He resents his brother’s freedom and the gracious forgiveness of their father. He is angry that his service and sacrifice haven’t been noticed and applauded and so he blames his father and villainises his brother (“But when this son of yours returned, after gobbling up your estate on prostitutes, you slaughtered the fattened calf for him.’ v.30—emphasis mine). Clearly, there is a second shadow at work in this parable.

The first two verses of Luke 15 give us a window into Luke’s editorial purpose in telling this story at this point in his Gospel:

All the tax collectors and sinners were gathering around Jesus to listen to him. The Pharisees and legal experts were grumbling, saying, “This man welcomes sinners and eats with them.”

This story, and the two ‘lost things’ parables that precede it, are Jesus’ response to the judgement and resentment of the legalistic, self-righteous religious leaders. The older brother is a mirror that invites them to explore their shadow and decide for themselves whether it is more important to maintain ritual purity than to celebrate broken people finding life and wholeness. Significantly, Jesus didn’t end his parable—he left his audience to decide for themselves what the brother’s response to the father’s pleading would be. I wonder if anyone in the crowd turned to the Pharisees and legal experts to see what they would do.